This is a question that has been spinning around in my head for some time now. I’m on the train right now, returning home after 3 fun and inspiring days at the Vitalis conference in Gothenburg. One issue that we however kept returning to in different sessions, is this eagerness to protect patients from worrying.

When we discuss patients’ online access to their medical records healthcare professionals are concerned that it will cause worry when patients don’t fully understand or when they can read information that really is worrying (perhaps lab results that are not normal, or evidence of illness). It’s even discussed that healthcare professionals will keep certain information out of the medical record in order to protect the patient from worrying.

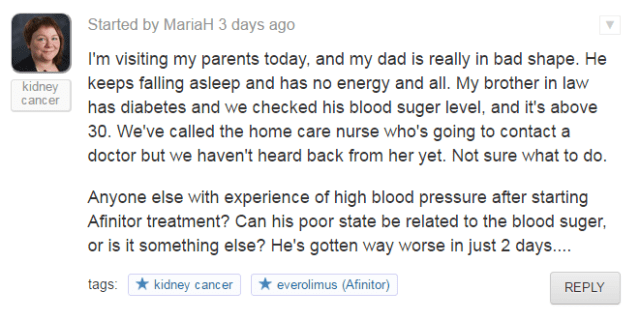

So, I’m wondering – how dangerous is it to worry? I realize that there are people who worry TOO much, and who’s lifes are negatively affected by this worry – but most of us are worried from time to time, right? Whether it’s about the loan on the house, paying rent, meeting that deadline at work, breaking up with your boyfriend or passing an important exam – we worry. It’s not a great place to be in – but it seems a normal reaction to a stressful situation. And of course we worry about our health. But healthcare professionals are often very eager to protect us from “unnecessary worry”, and they will keep their early hypothesis from us (if it’s not cancer – why cause unnecessary worry?). But is that really fair? Is it not our right to be able to prepare for potentially bad news when it comes to our health too? If the risk is very small – that can surely be communicated too. And trust me – when it comes to our health, we worry regardless – and we rarely seek healthcare without being already at least a little worried.

In a recent Facebook conversation, Cristin Lind (among many other things author of the great blog Durga’s toolbox) pointed out that sometimes it can be even better to acknowledge a person’s worry and ensure that all concerns are addressed. This really resonates with me. Sometimes when you seek healthcare, you’re worrying as much about whether they will really take you seriously and properly investigate your problems, as you worry about your actual health issue. Having someone acknowledge that there is cause for worrying and that examinations are needed to exclude serious conditions can be a relief. If it turns out there was no real cause for alarm – that’s only good news, and if the news are bad, at least you had some warning.

On good days – I think that healthcare professionals are trying to shield us from as much suffering as possible by filtering out information that could possibly make us worried. I’m still frustrated though when faced with this paternalistic approach.

On bad days (like today) – I can’t help but think that healthcare professionals are really protecting themselves from having difficult conversations, why should I bring up cancer if it turns out not to be? And if I say that I’m taking these tests to rule out a serious condition, the patient will surely be much more eager to find out the results as soon as possible – which can cause extra phone calls and add to my work load. I know I sound cynical, and I hate to be, but some days I am.

I would love to hear your thoughts on this;

- if you’re a patient or caregiver, do you want to be protected from unnecessary worry?

- if you’re a healthcare professional – how do you address this in your work practice and why?

And is there any good research on the pros and cons of different approaches to handling worrying information?

Please comment!

[post 29 in the #blogg100 challenge – yes, I’m way behind, but I’ll keep using the hashtag and linking to my posts anyway…]